Both Particle and Wave: Reading Scripture Theologically

Reflections on the Bible's paradoxes, with a postscript on Walter Brueggemann's passing

To my shock and surprise, a couple years ago I got asked to co-author a textbook on the Pentateuch with my friend Dave Beldman for Baker’s Reading Christian Scripture series. This was not the kind of writing project I’d have gone looking for, not least because I’m not fit to carry the scholarly sandals of many of the other contributors.

I said yes because I got excited about helping students encounter the Torah for the first time in an academic setting. On the one hand, I’m increasingly convinced that the Torah is “ground zero” for helping God’s people live more faithfully in relation to creation, politics, ethnicity, justice, immigration, economic life, and so much more. On the other hand, many Christians struggle to understand what strikes them as the bizarre, brutal bits of this part of the canon; as a result, the Torah can become a faith killer. I’m hoping this textbook can help students hear and respond to the outrageously good news of God and God’s ways proclaimed in the Pentateuch.

Reading the Old Testament Theologically

An unexpected gift of the writing process has been the need to wrestle more deeply with what it means to read the Old Testament theologically. It seems to me that reading theologically requires us to read in God’s presence, trusting God’s goodness, willing to be changed by our encounter, and appreciative of the mystery that such an encounter entails. This week, I thought I’d share a short selection I’ve been working on related to the mystery-appreciating aspect of reading the Old Testament well.

reading theologically means reading Scripture with an appreciation of the kind of mystery and paradox that must exist whenever creatures try to speak faithfully about our Creator. Indeed, “mystery is the lifeblood of theological reflection” on Scripture. Why? Because as theological readers of Scripture, we stand “before God the incomprehensible One.”1 As Isaiah puts it:

As the heavens are higher than the earth,

so are [God’s] ways higher than [our] ways

and [God’s] thoughts than [our] thoughts (Isa 55:9).

At the same time, Scripture teaches us that this “Incomprehensible One” draws near to humanity and chooses to reveal Godself to human creatures! While we cannot know God exhaustively or completely—how could we!—we can know God partially and truly. Why? Because God desires to be known, and accomplishes that desire, in part through Scripture. As the Isaiah passage quoted above goes on to say, despite the fact that Yahweh’s ways and thoughts are infinitely higher than ours, Yahweh’s word does not return to him empty, but accomplishes what God desires and achieves the purpose for which it was sent (Isa 55:11).

This may all seem a bit heady and impractical, but the implications for interpreting the OT are tremendous. Because the God who speaks in the Bible speaks in human language that we can understand, theologians have argued he accommodates himself to “our human language and condition.”2 As Calvin puts it, God “lisps with us as nurses are wont to do with little children,” accommodating “the knowledge of him to our feebleness. In doing so, he must, of course, stoop far below his proper height.”3

One way the OT accommodates us is by nearly always using metaphors to describe God.4 Metaphors speak of one thing in terms of another: “love is a rose,” “God is a Rock.” Theologically speaking, our Creator can be described truthfully by reference to creation precisely because creation reflects our Creator’s character—creation bears, to use another metaphor, the fingerprints of God.

Yet because our Creator is infinitely beyond creation and distinct from it, such metaphorical language communicates only partial truth, and this requires us to interpret metaphorical language theologically. Indeed, the key to all metaphors is the recognition that the two terms are alike in some ways, but different in other ways. Love is like a rose in its beauty and capacity for growth, but unlike a rose in that you better not fertilize it with manure. This dynamic gives metaphoric language much of its power, because we must ponder the way the two terms are similar and dissimilar. We wonder, for instance, whether love, like a rose, has thorns.

So far, so good, but matters are even more complex. I can say truthfully that I love my children and that God loves God’s children. But does that word love mean exactly the same thing when describing my human affection and God’s divine affection? Theologians have traditionally tried to say that while there is a connection between the way we use the word “love” in these two contexts, they are not precisely the same, not least because divine love is exercised by a God whose ways and thoughts are infinitely higher than our ways and thoughts.5 Because God is Creator of all things, depictions of God drawn from creation can truly “get at” something about God; because God is Creator and not creation, those depictions cannot give us complete, exhaustive knowledge about God. “God outdistances all our images; God cannot finally be captured by any of them.”6

…

Consider an example: Gen 6:6 tells us that God “regrets” having made human beings on the earth and that his heart is “greatly troubled.” Elsewhere Scripture seems to tell us that God does not change his mind, but the Flood story depicts Yahweh seriously altering his prior proceedings with humanity based on this “regret.” This doesn’t sound, on the surface at least, like the immutable, omniscient God!

What are we to make of this? Taking the depiction of God in the Flood story as an example, some so emphasize God’s otherness that they risk rejecting Scripture’s own witness; while it sounds like Yahweh was “greatly troubled” and changed course, we know God is immutable and unchanging, so God’s troubled regret is just deeply metaphorical language so accommodated to our creatureliness that it doesn’t tell us very much about God. This comes dangerously close to rejecting what Scripture itself says, replacing biblical language with language derived elsewhere. It's also naïve; all language about God, including words like “immutable,” are accommodations (this doesn’t mean that traditional theological language is necessarily bad, only that it cannot escape the intrinsically accommodated, metaphorical nature of creaturely speech about the Creator).

At the other extreme, some read Genesis as describing a God who is so completely captured by the biblical language of God’s regret that God is understood as constantly changing his mind, learning new things, discovering his own divine powerlessness to affect this or that outcome. We end up with a God who is “unsettled,” “uncertain, indecisive, ambiguous, and conflicted.”7 The problem with this view is both that it stands in tension with huge swaths of the biblical witness, and that it ignores the way theological language is always accommodated language. When Genesis tells us Yahweh regretted creating humanity, that must tell us something true about God, but it does not tell us that God’s regretting is exactly like human regretting. What it means for God who is the “Alpha and Omega” to regret creating humanity, and what it would mean for us to regret having done so, must be different.

Interpreters will have to wrestle with these mysteries as they grapple with the Pentateuch, and different theological traditions will settle in somewhat different places. Our purpose here is simply to identify that this mysterious, paradoxical dimension of Scripture is a feature rather than a bug. Nor is this just a fancy way of saying that the Bible is irrational or contradictory. In fact, mysterious paradoxes are part and parcel of everyday life, including even scientific study of the “natural world.”

Consider, for instance, one of the weirdest insights of quantum physics: the “particle-wave duality” of light. Scientists used to argue about whether light was a particle or a wave, given that particles and waves act differently. Today, quantum physics recognizes that light acts like both a particle and a wave, and indeed, that light appears to act like one or the other based on whether or not a scientist is observing it!8 Quantum physics can describe this reality, but it cannot explain it. The best answer to the question: “is light a particle or a wave?” requires scientists to make two statements that seem mutually contradictory. But the fact that it seems contradictory doesn’t mean it isn’t true! Nor, indeed, does it make the insight impractical; quantum physics has helped scientists make supercomputers, smartphones, and MRI machines.9

Apparent contradictions and mysterious paradoxes may seem embarrassing, but both in science and Scripture they can gesture toward deep truths and important breakthroughs. When the Bible makes a strong claim about God’s utter sovereignty in one text, and then an equally strong statement about human agency in another, it’s easy to see these as irrational contradictions. When the Bible boldly declares that God does not change his mind in one text, only to declare with equal insistence that he has changed his mind in a specific instance, it’s easy to either write this off as irrational or just pick whichever text we prefer. But if we read theologically, if we read with an appreciation of the mystery and paradox of human speech about God, we can see this as a kind of intentional “double speak,” a speaking twice in order to try to capture a paradox or mystery inherent in our limited understanding of the God who sits on high. Just as scientists simply have to move forward accepting the claim that light does act like a particle and a wave, Scripture calls us to receive and live into many truths that are rife with paradox and tension. To do otherwise is simply to reject the God who speaks through Scripture; after all, “the name the OT gives to a God whose ways are like mine is an idol.”10

What this appreciation of mystery means practically is that reading theologically demands humility and trust. Such humble, trusting reading of the revealed mysteries of God, however, leads us “further up and further in” to a life of praise.

The opportunity to wrestle with the Old Testament for a living has been one of the great privileges of my life. A few weeks back, I wrote about how the political complexity of Proverbs is a gift for Christians living a politically complex world. But the longer I spend in OT texts, the more often I’m struck with the fact that these texts are just obsessed with God. Their authors stake their lives on this God they cannot explain, pin down, or constrain. If we’re willing to take them seriously, if we allow them to welcome us a bit closer to the divine mystery rather than demand that they explain that mystery away, we may feel the sudden urge to take our shoes off. We will discover that we are standing on holy ground.

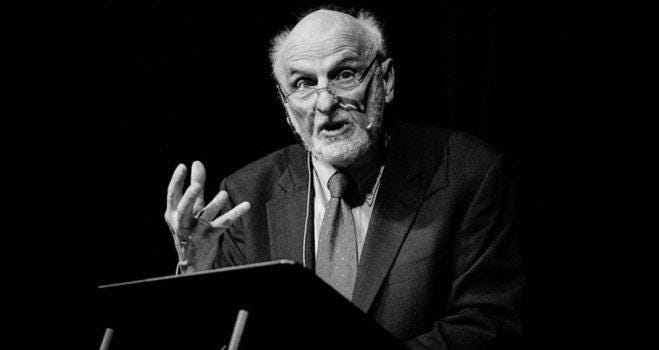

Postscript: A Rambling, Personal Reflection on Walter Brueggemann

Last week, Walter Brueggemann died at 92 years of age. Brueggemann was, without a doubt, the most influential Old Testament scholar of his generation, and reflections from numerous friends and colleagues will no doubt be coming out for a long time (check out this one from my friend Brent Strawn, for instance).

I only met Brueggemann a few times, but he nevertheless had a tremendous influence on me. When I was working on an ag development project in Kenya in my early 20s and trying to decide whether to go back to school for theology or development studies, his classic The Prophetic Imagination was one of three books that convinced me I had to go to seminary.11 Brueggemann argued that there was something revolutionary, even explosive about the Torah; he opened my eyes to the manna economy of abundance and to the sabbath as an act of resistance to Pharaoh’s totalizing regime. His influence is all over Robby Holt, Brian Fikkert, and my book, Practicing the King’s Economy: Honoring Jesus in How We Work, Earn, Spend, Save, and Give. When I wrote a cold call email to Brueggemann to ask him for an endorsement, he asked me to send him the hard copy. I nervously printed it out and put it in the mail. I’ll never forget receiving the email from him in response: “I love your book!” The fact that such a legend took the time to read an unpublished manuscript by somebody he’d never heard of meant the world to me, and speaks to his generosity as a scholar.

The Prophetic Imagination is probably his most famous book, but Brueggemann also wrote a series of essays that transformed psalms scholarship. Indeed, his essay “The Costly Loss of Lament” placed the lament psalms back on the church’s map. If you’ve ever heard a sermon about lament, that sermon probably was influenced, directly or indirectly, by Brueggemann’s work (his collection of essays on the psalms, From Whom No Secrets Are Hid, is outstanding). His emphasis on the importance for lament both in terms of authentic personal faith and the quest for justice deeply influenced my own efforts to wrestle with the psalter’s justice songs in Just Discipleship and elsewhere.

Much of my work in community development was shaped by community organizer John McKnight’s Asset Based Community Development approach (the idea that we start with the gifts, assets, abilities, and dreams of a community rather than the problems, liabilities, and needs). Brueggemann’s passion for the Scripture’s witness to “neighborliness” led him to collaborate with McKnight on many projects. I vividly remember being sent by a non-profit to a training McKnight and Brueggemann were doing in Memphis, and then chatting with Brueggemann on break about whether I should go on to do a PhD.

One more story. Another great privilege of my life was working with Advance Memphis, an organization that helps adults from the South Memphis neighborhood that was our home for 12 years find jobs, get their finances in order, earn their GED, start a small business, etc. During my time at Advance, I went and heard Brueggemann give a talk. He was, as usual, relentless in his criticism of the way that so much of our culture and imagination has been bound by the totalizing power of idolatrous consumerism. We’d been sucked in to false ways of being in the world, and of partnering with economic and political ideologies that destroy the possibility of neighborliness. At one point, he had a few throw away lines about how Joseph saved the Egyptians, but only by enslaving them. He, too, had been caught up in Pharaoh’s totalizing society and economy.

By the end, I couldn’t help but wonder: am I just working for Pharaoh? Is my work helping people find entry-level jobs simply greasing the wheels for an irredeemable system? With fear and trepidation, I stood up and asked him.

“No, you’re like Daniel,” Brueggemann growled (he had an amazing southern accent). “You work in the empire, just make sure you remember your name and refuse to eat the Babylonian food. And when you get the chance, speak up like Daniel did for the rights of the poor and the oppressed.”

It was an amazingly pastoral moment, one made possible by Brueggemann’s saturation in Holy Scripture. With a few lines, he not only encouraged me in my work, but also gave me a new framework. It is possible that we become complicit with dehumanizing forces even in our efforts to love our neighbors; but it’s also possible to “seek the good” in Babylon like Daniel did, if we’re willing to embrace the kind of prophetic imagination that includes both prophetic criticizing (including self-criticizing!) and prophetic energizing, to use the language of The Prophetic Imagination.

That moment not only influenced me personally, it also affected the trajectory of my scholarship. There’s no doubt that Brueggemann’s understanding of the nature of Scripture’s authority was different than mine; I liked the idea that Joseph and Daniel might provide some contrasts, but I knew I had to see if that really made sense of what Scripture said for myself. That’s why Just Discipleship includes an entire chapter for each figure, both of which, I hope, confirm and extend those powerful insights Brueggemann made offered in a few off hand sentences so many years ago.

In fact, when I went back and looked at the few emails I exchanged with Brueggemann, I discovered that, years ago, I was already beginning to imagine a book on the Bible’s subversive, surprising, complex political teaching. Already back then, Brueggemann not only encouraged me to pursue that project, but gave me advice on who to read along the way. That book will come out next year, and is the foundation for an MA course on the Bible and Politics I’m teaching right now. In so many ways, the seed for that book was planted when the world’s leading OT scholar took the time to offer a brilliant pastoral word and some academic advice to a young kid trying to love Jesus by helping his neighbors find jobs.

As I say, Brueggemann had a different approach to Scripture than my essentially evangelical one. I think he’s always worth reading, even when I find plenty of serious points of disagreement. But while Brueggemann didn’t talk about the authority of Scripture the way we evangelicals do, the truth is, he often took the text in front of him more seriously than most of us. That’s why his work has proved so widely influential. I’ve heard Brueggemann quoted by progressive activists during marches against racism and in evangelical pulpits calling us to embrace Sabbath rest. Because Brueggemann loved the text, because, as one colleague of his said of him in his own reflections, he believed that the world would be changed as the Word was preached, he has proven to be a remarkable dialogue partner for Christians of all stripes.

I can’t remember where I heard this, but somebody told me that he would always ask students in class: “What would we know about God, the world, and ourselves, if this was the only text we had?” That’s such a powerful, transformative question. His willingness to wrestle with the text in all of its beauty, strangeness, and diversity invites us to not only read the text better, but to draw nearer to the wild, strange, undomesticated God who speaks through that text. I am grateful to Jesus for his work, and for the small but substantial personal interactions we had that affected me so much. He will be missed.

Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics: Abridged, John Bolt, trans. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2011), 147.

Bavinck, Dogmatics, 168.

John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, Henry Beveridge, trans., I.xiii.1 (available online at https://www.ccel.org/ccel/calvin/institutes.toc.html, accessed November 28, 2023).

Terence E. Fretheim, The Suffering of God: An Old Testament Perspective (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress, 1985), 5.

See Alan Torrance, “Analogy,” DTIB, 38-40.

Fretheim, Suffering, 8.

Fretheim’s depiction of aspects of Brueggemann’s depiction of God in Terence E. Fretheim, What Kind of God? Collected Essays of Terence E. Fretheim, Michael J. Chan and Brent A. Strawn, eds. (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2015), 78.

For an easyish description, see Daisy Dobrijevic, “The Double-Slit Experiment: Is Light A Wave or a Particle?” Space (March 23, 2022), https://www.space.com/double-slit-experiment-light-wave-or-particle, accessed November 28, 2023.

Chad Orzel, “What Has Quantum Mechanics Ever Done for Us?” Forbes (August 13, 2015), https://www.forbes.com/sites/chadorzel/2015/08/13/what-has-quantum-mechanics-ever-done-for-us/?sh=27303eb94046, accessed November 28, 2023.

Christopher Seitz, “Canon and Conquest” in Divine Evil? The Moral Character of the God of Abraham, Michael Bergmann et. al, eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 293.

The other two were NT Wright’s The New Testament and the People of God and Richard Hays’ Moral Vision of the New Testament.

A helpful tribute, Michael! This inspires me to engage more with Brueggemann!